El pasado 3 de diciembre Niles Eldredge dio una charla en el auditorio Herman Niemeyer del edificio milenio de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Universidad de Chile. La charla fue básicamente sobre la investigación histórica de Niles de la vida de Darwin: entre otros detalles mencionó cómo el hallazgo de un Capibara fósil de gran tamaño había sido descrito por Darwin, ya en sus notas en el Beagle, como un posible ancestro del Capibara actual. Eldredge dejó en claro que, dado su abuelo Erasmo, y un influyente profesor evolucionista que tuvo en escocia, Darwin tuvo siempre a la evolución en mente antes y durante su viaje del Beagle, pese a que después afirmara haber llegado la conclusión de la evolución sólo después de su viaje, y como mero resultado de numerosas y meticulosas observaciones empíricas. Tramposín! Por motivos quizás "políticos" Darwin explotó aquel "mito" del quehacer cientifico, a sabiendas de su falsedad. Eldredge también habló de la "genialidad" de Darwin en haberse dado cuenta del operar de la selección natural a partir del principio maltusiano de la superproductivifdad, combinado con el hecho de la existencia de variaciones hereditarias... momentos de la charla en los que yo sacudía enfáticamente la cabeza de lado a lado, fastidiado. Al finalizar la charla le hice una pregunta al respecto. Si la superproductividad siempre está produciendo competencia entre las distintas variantes, porqué la estasis es lo más común en el registro fosil? No debería haber siempre evolución darwiniana por competencia? Como había dicho el mismo Eldredge alguna vez, junto a su camarada Gould, "Stasis is Data", es decir, es un hecho que las especies pueden pasar millones de años sin cambiar. Un hecho que nos dice algo.

El pasado 3 de diciembre Niles Eldredge dio una charla en el auditorio Herman Niemeyer del edificio milenio de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Universidad de Chile. La charla fue básicamente sobre la investigación histórica de Niles de la vida de Darwin: entre otros detalles mencionó cómo el hallazgo de un Capibara fósil de gran tamaño había sido descrito por Darwin, ya en sus notas en el Beagle, como un posible ancestro del Capibara actual. Eldredge dejó en claro que, dado su abuelo Erasmo, y un influyente profesor evolucionista que tuvo en escocia, Darwin tuvo siempre a la evolución en mente antes y durante su viaje del Beagle, pese a que después afirmara haber llegado la conclusión de la evolución sólo después de su viaje, y como mero resultado de numerosas y meticulosas observaciones empíricas. Tramposín! Por motivos quizás "políticos" Darwin explotó aquel "mito" del quehacer cientifico, a sabiendas de su falsedad. Eldredge también habló de la "genialidad" de Darwin en haberse dado cuenta del operar de la selección natural a partir del principio maltusiano de la superproductivifdad, combinado con el hecho de la existencia de variaciones hereditarias... momentos de la charla en los que yo sacudía enfáticamente la cabeza de lado a lado, fastidiado. Al finalizar la charla le hice una pregunta al respecto. Si la superproductividad siempre está produciendo competencia entre las distintas variantes, porqué la estasis es lo más común en el registro fosil? No debería haber siempre evolución darwiniana por competencia? Como había dicho el mismo Eldredge alguna vez, junto a su camarada Gould, "Stasis is Data", es decir, es un hecho que las especies pueden pasar millones de años sin cambiar. Un hecho que nos dice algo.

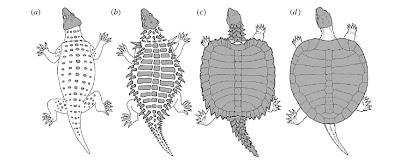

Odontochelys is the new basalmost triassic turtle, with a plesiomorphic ("primitive") presence of teeth (hence the name) and a most remarkable transitional aspect: It has a perfectly formed plastron yet no carapace. Odontochelys only presents the dorsal midline of the neural plates of the carapace, that are close to the neural spines but remain separate (which is not the case in more derived turtles).

Odontochelys is the new basalmost triassic turtle, with a plesiomorphic ("primitive") presence of teeth (hence the name) and a most remarkable transitional aspect: It has a perfectly formed plastron yet no carapace. Odontochelys only presents the dorsal midline of the neural plates of the carapace, that are close to the neural spines but remain separate (which is not the case in more derived turtles). of the dermis surrounding the rib. Because of this paracrine effect on the dermis, Gilbert hypothesized that a single-step shift of the ribs to the dermis could have induced the origin of a well-formed carapace.

of the dermis surrounding the rib. Because of this paracrine effect on the dermis, Gilbert hypothesized that a single-step shift of the ribs to the dermis could have induced the origin of a well-formed carapace.

Cebra-Thomas JA, Betters E, Yin M, Plafkin C, McDow K, Gilbert SF. 2007 Evidence that a late-emerging population of trunk neural crest cells forms the plastron bones in the turtle Trachemys scripta. Evol Dev. 9(3):267-77.

Cebra-Thomas J, Tan F, Sistla S, Estes E, Bender G, Kim C, Riccio P, Gilbert SF. 2005. How the turtle forms its shell: a paracrine hypothesis of carapace formation. J Exp Zoolog B Mol Dev Evol. Nov 15;304(6):558-69.

Al fin tenemos una filogenia molecular que evalúa si las aves son más cercanas a los dinosaurios que a los cocodrilomorfos como indica la cladistica morfológica. Nótese además que se incluyó colágeno de un mamut. La única anomalía en todo el árbol es la posicón de Anolis un nodo demasiado hacia afuera (deberia ser grupo hermano de archosauria, no de amniota). Nada de mal para dos proteínas incompletas!!

Al fin tenemos una filogenia molecular que evalúa si las aves son más cercanas a los dinosaurios que a los cocodrilomorfos como indica la cladistica morfológica. Nótese además que se incluyó colágeno de un mamut. La única anomalía en todo el árbol es la posicón de Anolis un nodo demasiado hacia afuera (deberia ser grupo hermano de archosauria, no de amniota). Nada de mal para dos proteínas incompletas!! Two different birds species illustrating the fibular crest of the tibia, upwards, rectangle-shaped (from Müller and Streicher 1989)

Two different birds species illustrating the fibular crest of the tibia, upwards, rectangle-shaped (from Müller and Streicher 1989)  The fibular crest is an apomorphy of theropod dinosaurs. On the left, a theropod; right, a non-theropod dinosaur (Müller and Streicher 1989)

The fibular crest is an apomorphy of theropod dinosaurs. On the left, a theropod; right, a non-theropod dinosaur (Müller and Streicher 1989)

Hi Coturnix,

I haven' heard yet much criticism of the Berger et al. paper, so I guess I'll be one of the first.

I consider that Berger hasn't really established that these tiny Palauans are H. sapiens. This could be a species close to H. sapiens (perhaps the closest known so far and thus "sister" species) that has retained some plesiomorphic traits yet shares several apomorphies with H. sapiens (until now thought to be "autapomorphies", exclusively of sapiens)

To discard this possibility and prove that tiny Palauans are H. sapiens, Berger et al. would have to show that their tiny Palauans are phylogenetically nested within H. sapiens (and not "right outside"). However they did not make a phylogenetic analysis (despite disposing of several specimens and good morphological data)

Without that, they are simply preferring hypotheses of convergence or reversal rather than homology for the primitive traits, which is contra-parsimony unless further evidence is provided; and for that, they would need phylogenetic analysis.

Resulta que el desarrollo de plumas metatarsales en la crianza de aves domésticas es tan común que tiene su propio término: Ptilopodia. Nótese además que en esta raza contamos con la buena fortuna de que las plumas de las alas se distinguen además por su color negro, reforzando la noción de la naturaleza "alar" de las plumas metatarsales. Surgen algunas preguntas inmediatas...son estas plumas asimétricas (aerodinámicas)? Cómo es la expresión de Tbx5?

Resulta que el desarrollo de plumas metatarsales en la crianza de aves domésticas es tan común que tiene su propio término: Ptilopodia. Nótese además que en esta raza contamos con la buena fortuna de que las plumas de las alas se distinguen además por su color negro, reforzando la noción de la naturaleza "alar" de las plumas metatarsales. Surgen algunas preguntas inmediatas...son estas plumas asimétricas (aerodinámicas)? Cómo es la expresión de Tbx5?

¿Qué habría dicho el funcionalista Cuvier? A él le parecía perfectamente armonioso y "adaptado" que un animal con rumen y pezuñas fuera herbívoro, pero vemos que este funcionalismo no ayuda mucho a prever la realidad de la diversidad biológica. Recuerdo además la especilización herbívora de los dientes en algunos crocodílidos notosuchidae. Dudo que Cuvier habría podido predecir eso tampoco.

¿Qué habría dicho el funcionalista Cuvier? A él le parecía perfectamente armonioso y "adaptado" que un animal con rumen y pezuñas fuera herbívoro, pero vemos que este funcionalismo no ayuda mucho a prever la realidad de la diversidad biológica. Recuerdo además la especilización herbívora de los dientes en algunos crocodílidos notosuchidae. Dudo que Cuvier habría podido predecir eso tampoco.

Sus extremidades anteriores son notables: aunque son relativamente pequeñas son claramente especializadas. El especimen de la foto con el close up es un Mononykus olecranus. El nombre hace referencia a que presenta un sólo gran dedo (el dedo 1) y que la ulna presenta un gran olecranon o sitio de inserción para el músculo extensor. Presenta además una quilla esternal (flecha) de inserción de musculatura. Biomecánicamente es casi igual al brazo de un topo.

Sus extremidades anteriores son notables: aunque son relativamente pequeñas son claramente especializadas. El especimen de la foto con el close up es un Mononykus olecranus. El nombre hace referencia a que presenta un sólo gran dedo (el dedo 1) y que la ulna presenta un gran olecranon o sitio de inserción para el músculo extensor. Presenta además una quilla esternal (flecha) de inserción de musculatura. Biomecánicamente es casi igual al brazo de un topo.