A diferencia de la morfología functional, que puede estudiarse en laboratorio, o en el registro fósil, sin necesidad de conocer el contexto natural en el que se desenvuelve el organismo, ya que se centra en la relación entre la estructura y función de un rasgo en particular, la ecomorfología es una aproximación centrada en todos los aspectos del fenotipo, no en algunos rasgos en particular y se sirve de la morfología funcional dándole un contexto biológico.

Por ejemplo la convergencia ocular, i.e., la orientación frontalizada de los ojos, se observa en una gran cantidad de linajes, como en aves nocturnas y/o cazadoras, como también en mamíferos como los carnívoros (placentados y marsupiales) o primates. En alguna medida en roedores nocturnos también se observa un grado de convergencia ocular mayor que en sus linajes hermanos de actividad diurna (tesis de Tomás Vega).

Cristopher Heesy (2008) analizó cráneos de un gran número (321) de taxa de mamíferos actuales y correlacionó el grado de convergencia con diversos aspectos del modo de vida. Evaluó cuales aspectos del fenotipo ontogénico, como el patrón de actividad (diurno/nocturno), la preferencia de sustrato (aéreo/arborícola/terrestre) y el grado de faunivoría guardaban relación con el grado de convergencia.

Fig 1. Campo visual de la ardilla (a,b) y del lémur (c,d). Tomado de Hessy 2008.

Fig 1. Campo visual de la ardilla (a,b) y del lémur (c,d). Tomado de Hessy 2008.Linajes nocturnos y crepusculares (tanto marsupiales como placentados) mostraron mayor convergencia ocular que los diurnos. Los placentados carnívoros (tanto diurnos como nocturnos) mostraron mayor convergencia que los forrajeros oportunistas o no-carnívoros. Sin embargo, no encontraron asociación entre convergencia y la preferencia de sustrato. Tales resultados son consistentes con el hecho de que la visión binocular permite detectar profundidad (la estereópsis es buena para los depredadores) y aumenta la agudeza visual (nocturnos), mientras que un mayor campo visual, en desmedro de la binocularidad, permite detectar al depredador en espacios abiertos como las praderas.

Una predicción importante de la filoepigénesis: Similitud en ecomorfologías implican una similitud en los fenotipos ontogénicos.

Por ejemplo en distintos linajes de mamíferos se pueden reconocer varias ecomorfologías, como forma de hormiguero, cola prensil, ojos frontalizados, etc. Lo más iluminador es que en cada linaje uno puede reconocer casi todos los modos de vida asi como sus especializaciones morfológicas.

Fig 2. Distintos ecomorfotipos ocurren en cada linaje.

De hecho, esto fue la causa de que la filogenia de mamíferos fuera un caos mientras se consideraban rasgos morfológicos en las reconstrucciones: todos los linajes tenian todos los ecomorfotipos, por lo que no fue hasta el advenimiento de reconstrucciones basadas en eventos moleculares raros que se pudo tener un esquema más claro de la filogenia de mamiferos existentes (ver Springer et al 2004).

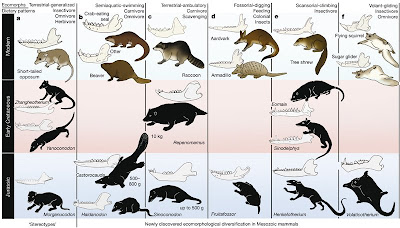

Lo más bello de todo es que esta ubicuidad de modos de vida y morfos similares también ha ocurrido en tiempos remotos, a modo de experimentos evolutivos en linajes ancestrales de igual manera que en linajes actuales, como la siguiente figura aparecida en el paper de Zhe-Xi Luo (2007), el cual es tan iluminador que merecería su post propio.

Fig 3. Experimentos evolutivos de mamíferos del Mesozoico y su convergencia ecológica con ecomorfotipos de mamíferos modernos. Ecomorfos: a) terrestre insectivoro/omnivoro, b) Carnivoro/omnivoro semiacuático, c) carnivoro oportunista/terrestre, d) fosorial, cavador/hormiguero, e) trepador/insectívoro, f) planeador/omnívoro. En celeste: Jurásico, rosa: Cretásico temprano, blanco: actual.

Abrazos,

Rodrigo Suárez.

Wainwright PC (1991) Ecomorphology: Experimental Functional Anatomy for Ecological Problems. American Zoologist; 31(4):680-693

Bock WJ (1994) Concepts and methods in ecomorphology. J. Biosci.; 19(4):403-413.

Hessy CP (2008) Ecomorphology of orbit orientation and the adaptive significance of binocular vision in primates and other mammals. Brain Behav Evol;71(1):54-67.

Luo ZX (2007) Transformation and diversification in early mammal evolution. Nature;450(7172):1011-9