El pasado 3 de diciembre Niles Eldredge dio una charla en el auditorio Herman Niemeyer del edificio milenio de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Universidad de Chile. La charla fue básicamente sobre la investigación histórica de Niles de la vida de Darwin: entre otros detalles mencionó cómo el hallazgo de un Capibara fósil de gran tamaño había sido descrito por Darwin, ya en sus notas en el Beagle, como un posible ancestro del Capibara actual. Eldredge dejó en claro que, dado su abuelo Erasmo, y un influyente profesor evolucionista que tuvo en escocia, Darwin tuvo siempre a la evolución en mente antes y durante su viaje del Beagle, pese a que después afirmara haber llegado la conclusión de la evolución sólo después de su viaje, y como mero resultado de numerosas y meticulosas observaciones empíricas. Tramposín! Por motivos quizás "políticos" Darwin explotó aquel "mito" del quehacer cientifico, a sabiendas de su falsedad. Eldredge también habló de la "genialidad" de Darwin en haberse dado cuenta del operar de la selección natural a partir del principio maltusiano de la superproductivifdad, combinado con el hecho de la existencia de variaciones hereditarias... momentos de la charla en los que yo sacudía enfáticamente la cabeza de lado a lado, fastidiado. Al finalizar la charla le hice una pregunta al respecto. Si la superproductividad siempre está produciendo competencia entre las distintas variantes, porqué la estasis es lo más común en el registro fosil? No debería haber siempre evolución darwiniana por competencia? Como había dicho el mismo Eldredge alguna vez, junto a su camarada Gould, "Stasis is Data", es decir, es un hecho que las especies pueden pasar millones de años sin cambiar. Un hecho que nos dice algo.

El pasado 3 de diciembre Niles Eldredge dio una charla en el auditorio Herman Niemeyer del edificio milenio de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Universidad de Chile. La charla fue básicamente sobre la investigación histórica de Niles de la vida de Darwin: entre otros detalles mencionó cómo el hallazgo de un Capibara fósil de gran tamaño había sido descrito por Darwin, ya en sus notas en el Beagle, como un posible ancestro del Capibara actual. Eldredge dejó en claro que, dado su abuelo Erasmo, y un influyente profesor evolucionista que tuvo en escocia, Darwin tuvo siempre a la evolución en mente antes y durante su viaje del Beagle, pese a que después afirmara haber llegado la conclusión de la evolución sólo después de su viaje, y como mero resultado de numerosas y meticulosas observaciones empíricas. Tramposín! Por motivos quizás "políticos" Darwin explotó aquel "mito" del quehacer cientifico, a sabiendas de su falsedad. Eldredge también habló de la "genialidad" de Darwin en haberse dado cuenta del operar de la selección natural a partir del principio maltusiano de la superproductivifdad, combinado con el hecho de la existencia de variaciones hereditarias... momentos de la charla en los que yo sacudía enfáticamente la cabeza de lado a lado, fastidiado. Al finalizar la charla le hice una pregunta al respecto. Si la superproductividad siempre está produciendo competencia entre las distintas variantes, porqué la estasis es lo más común en el registro fosil? No debería haber siempre evolución darwiniana por competencia? Como había dicho el mismo Eldredge alguna vez, junto a su camarada Gould, "Stasis is Data", es decir, es un hecho que las especies pueden pasar millones de años sin cambiar. Un hecho que nos dice algo.domingo, diciembre 28, 2008

Niles Eldredge en la Universidad de Chile

El pasado 3 de diciembre Niles Eldredge dio una charla en el auditorio Herman Niemeyer del edificio milenio de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Universidad de Chile. La charla fue básicamente sobre la investigación histórica de Niles de la vida de Darwin: entre otros detalles mencionó cómo el hallazgo de un Capibara fósil de gran tamaño había sido descrito por Darwin, ya en sus notas en el Beagle, como un posible ancestro del Capibara actual. Eldredge dejó en claro que, dado su abuelo Erasmo, y un influyente profesor evolucionista que tuvo en escocia, Darwin tuvo siempre a la evolución en mente antes y durante su viaje del Beagle, pese a que después afirmara haber llegado la conclusión de la evolución sólo después de su viaje, y como mero resultado de numerosas y meticulosas observaciones empíricas. Tramposín! Por motivos quizás "políticos" Darwin explotó aquel "mito" del quehacer cientifico, a sabiendas de su falsedad. Eldredge también habló de la "genialidad" de Darwin en haberse dado cuenta del operar de la selección natural a partir del principio maltusiano de la superproductivifdad, combinado con el hecho de la existencia de variaciones hereditarias... momentos de la charla en los que yo sacudía enfáticamente la cabeza de lado a lado, fastidiado. Al finalizar la charla le hice una pregunta al respecto. Si la superproductividad siempre está produciendo competencia entre las distintas variantes, porqué la estasis es lo más común en el registro fosil? No debería haber siempre evolución darwiniana por competencia? Como había dicho el mismo Eldredge alguna vez, junto a su camarada Gould, "Stasis is Data", es decir, es un hecho que las especies pueden pasar millones de años sin cambiar. Un hecho que nos dice algo.

El pasado 3 de diciembre Niles Eldredge dio una charla en el auditorio Herman Niemeyer del edificio milenio de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Universidad de Chile. La charla fue básicamente sobre la investigación histórica de Niles de la vida de Darwin: entre otros detalles mencionó cómo el hallazgo de un Capibara fósil de gran tamaño había sido descrito por Darwin, ya en sus notas en el Beagle, como un posible ancestro del Capibara actual. Eldredge dejó en claro que, dado su abuelo Erasmo, y un influyente profesor evolucionista que tuvo en escocia, Darwin tuvo siempre a la evolución en mente antes y durante su viaje del Beagle, pese a que después afirmara haber llegado la conclusión de la evolución sólo después de su viaje, y como mero resultado de numerosas y meticulosas observaciones empíricas. Tramposín! Por motivos quizás "políticos" Darwin explotó aquel "mito" del quehacer cientifico, a sabiendas de su falsedad. Eldredge también habló de la "genialidad" de Darwin en haberse dado cuenta del operar de la selección natural a partir del principio maltusiano de la superproductivifdad, combinado con el hecho de la existencia de variaciones hereditarias... momentos de la charla en los que yo sacudía enfáticamente la cabeza de lado a lado, fastidiado. Al finalizar la charla le hice una pregunta al respecto. Si la superproductividad siempre está produciendo competencia entre las distintas variantes, porqué la estasis es lo más común en el registro fosil? No debería haber siempre evolución darwiniana por competencia? Como había dicho el mismo Eldredge alguna vez, junto a su camarada Gould, "Stasis is Data", es decir, es un hecho que las especies pueden pasar millones de años sin cambiar. Un hecho que nos dice algo.jueves, diciembre 25, 2008

Predicting the evolution of Theropod arm size

In 1999 I published an article in the (cryptic) monthly news bulletin of the Museum of Natural History of Chile, entitled "Evolution of Arm Size in Theropod Dinosaurs: A Developmental Hypothesis". In this work, which I did as an undergrad, I tackled what seemed a consistent trend among species of theropod dinosaurs, the presence of proportionally smaller arm sizes in species with larger body size. Femur size correlates quite directly with body size in dinosaurs: I therefore took femur size as an indicator of body size and making a linear regression I obtained that Humerus = 0,387 (Femur)^0,6807, with a rather nice determination coefficient, R^2 = 0,89. It is, of course, very remarkable that this negative allometry would so nicely predict theropod humerus size. Rather than the usual adaptive explanations, I presented a developmental hypothesis: The ontogeny of the most recent common ancestor of the theropods presented slower growth of the arm than of the leg, with arms that were proportionally larger earlier in ontogeny, at smaller body sizes. Thereafter, evolutionary variation of different body sizes in different species descended from this ancestor simply reflected conservation of this ontogenetic trait, with smaller- or larger-looking arms as a consequence of body-size variation, rather than any process of "local" adaptation. In this context, the very bird-like dromaeosaurid dinosaurs would owe their proportionally large arms to their small body size. If this were indeed correct, if a dromaeosaurid species would evolve a larger body size, we would expect it to show short arms, unlike those of its small-sized, long-armed ancestors.

viernes, diciembre 19, 2008

miércoles, noviembre 26, 2008

Quick comments on Odontochelys

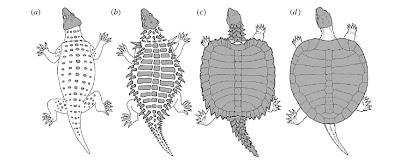

Odontochelys is the new basalmost triassic turtle, with a plesiomorphic ("primitive") presence of teeth (hence the name) and a most remarkable transitional aspect: It has a perfectly formed plastron yet no carapace. Odontochelys only presents the dorsal midline of the neural plates of the carapace, that are close to the neural spines but remain separate (which is not the case in more derived turtles).

Odontochelys is the new basalmost triassic turtle, with a plesiomorphic ("primitive") presence of teeth (hence the name) and a most remarkable transitional aspect: It has a perfectly formed plastron yet no carapace. Odontochelys only presents the dorsal midline of the neural plates of the carapace, that are close to the neural spines but remain separate (which is not the case in more derived turtles).Lets briefly recall what some evil saltationists (paleos and evo-devo's) have said about this. I remember Bob Bakker's book "The dinosaur heresies" (1986). There, he mentions the fact that in turtles the pectoral girdle is actually under the ribs, and points out that this qualitative aspect is hard to imagine to have occurred in more than a single step.

What can development tell us of all this? First, the plastron is derived from the neural crest, unlike the carapace, which is derived from a mixture of dermal bone and ribs. Second, the plastron ossifies before the carapace. Odontochelys reveals that this embryological and temporal separation also reflects a phylogenetic sequence. Scott Gilbert (yes, the book guy) points out that in turtles, the ribs have shifted dorsally, to developing within the dermis, a unique trait within amniotes. If an embryonic rib is experimentally inserted in the dermis of a chicken embryo, the result is ossification

of the dermis surrounding the rib. Because of this paracrine effect on the dermis, Gilbert hypothesized that a single-step shift of the ribs to the dermis could have induced the origin of a well-formed carapace.

of the dermis surrounding the rib. Because of this paracrine effect on the dermis, Gilbert hypothesized that a single-step shift of the ribs to the dermis could have induced the origin of a well-formed carapace.Some regard this hypothesis as incompatible with the hypothesis that an exoskeleton of separate dermal bones preceded the origin of the carapace. This incompatibility in my opinion is not quite so; dermal bones could have existed or not previous to the shift of the ribs closer to the dermis; the shift could have led to a single carapace. Critics to Gilbert's hypothesis have pointed out that in the carapace of the early (very fragmentary) triassic turtle Chinlechelys, ribs are not "immersed" in the carapace but run immediately below the surface of the dermal plates. However it is possible that this was sufficient for the paracrine effect leading to a single carapace "shell". Unfortunately we cannot know if the pectoral girdle was already under the ribs in Chinlechelys.

Even admitting the possibility of previous ostederms, Odontochelys is certainly something unexpected from the more "gradualist" perspective, which was "hoping" early stages of dermal armor would go back to remote Pareiasaur-like ancestors (see figure below). The full plastron of Odontochelys is pretty derived, yet this species has no "coat" of osteoderms.

References:

Li C, Wu X-C, Rieppel O, Wang L-T, Zhao L-J (2008) An ancestral turtle from the Late Triassic of southwestern China. Nature 456: 497-501

Joyce WG, SG Lucas, TM Scheyer, AB Heckert, AP Hunt (2008). A thin-shelled reptile from the Late Triassic of North America and the origin of the turtle shell Proceedings of the Royal Society B DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1196

Cebra-Thomas JA, Betters E, Yin M, Plafkin C, McDow K, Gilbert SF. 2007 Evidence that a late-emerging population of trunk neural crest cells forms the plastron bones in the turtle Trachemys scripta. Evol Dev. 9(3):267-77.

Cebra-Thomas J, Tan F, Sistla S, Estes E, Bender G, Kim C, Riccio P, Gilbert SF. 2005. How the turtle forms its shell: a paracrine hypothesis of carapace formation. J Exp Zoolog B Mol Dev Evol. Nov 15;304(6):558-69.

miércoles, noviembre 19, 2008

Paedomorphosis vs Adaptacionismo

Muchos habrán escuchado sobre uno de los rasgos más llamativos que presenta la paedomorphosis en la evolución de los seres humanos; si observamos un feto de 7 meses del chimpancé, vemos que presenta una distribución del pelaje como la de un ser humano, con el pelo concentrado sobre la cabeza. La verdad es que había escuchado este dato e incluso había visto un dibujo de la cabeza pero la verdad es que no existe reemplazo para una foto. Finalmente he encontrado una en la web, que originalmente fue publicada en el libro "The life of primates" de Adolph Schultz, (1969). Esto me ha permitido salir de algunas dudas. Puntualmente, hay pelo en la barbilla y los labios, como en el adulto humano; sin embargo, a diferencia del adulto humano, no hay pelo sobre los genitales. Aún me queda la pregunta de si hay pelo o no bajo los brazos. Otra novedad es que se observan cejas muy claramente demarcadas, que luego desaparecerán completamente (ver imagen a la izquierda). Notable!

Muchos habrán escuchado sobre uno de los rasgos más llamativos que presenta la paedomorphosis en la evolución de los seres humanos; si observamos un feto de 7 meses del chimpancé, vemos que presenta una distribución del pelaje como la de un ser humano, con el pelo concentrado sobre la cabeza. La verdad es que había escuchado este dato e incluso había visto un dibujo de la cabeza pero la verdad es que no existe reemplazo para una foto. Finalmente he encontrado una en la web, que originalmente fue publicada en el libro "The life of primates" de Adolph Schultz, (1969). Esto me ha permitido salir de algunas dudas. Puntualmente, hay pelo en la barbilla y los labios, como en el adulto humano; sin embargo, a diferencia del adulto humano, no hay pelo sobre los genitales. Aún me queda la pregunta de si hay pelo o no bajo los brazos. Otra novedad es que se observan cejas muy claramente demarcadas, que luego desaparecerán completamente (ver imagen a la izquierda). Notable!Es curioso que, pese a que este dato se conoce desde hace ya bastante tiempo, aún se discuten diferentes hipótesis adaptacionistas para explicar la concentración del pelo sobre la cabeza del ser humano; la más

popular es que esto evolucionó por selección para correr bajo el sol por largas distancias, lo cual, supuestamnete, le permitiría tener un cuerpo "refrescado" a la vez que se protegía al maratonista de la Sabana de la intensidad de los rayos del sol. Otras explicaciones citaban una supuesta menor vulnerabilidad a los parásitos, con selección sexual para explicar la permanencia del pelo sólo en la cabeza. Ninguna de estas hipóestis parece enterarse del hecho de que esta distribución se originó en la etapa fetal, donde claramente ninguno de estos factores fue relevante. Lo más gracioso es que, al confrontar a los adaptacionistas con este hecho (en discusiones en los blogs), tristemente no logran concederle ninguna relevancia; es una mera "coincidencia". No hay mejor ejemplo de cómo la ideología produce una cínica miopia intelectual incluso con los datos más evidentes. Hay quienes no se enterarían de la realidad aún si ésta les vomitase en los zapatos.

popular es que esto evolucionó por selección para correr bajo el sol por largas distancias, lo cual, supuestamnete, le permitiría tener un cuerpo "refrescado" a la vez que se protegía al maratonista de la Sabana de la intensidad de los rayos del sol. Otras explicaciones citaban una supuesta menor vulnerabilidad a los parásitos, con selección sexual para explicar la permanencia del pelo sólo en la cabeza. Ninguna de estas hipóestis parece enterarse del hecho de que esta distribución se originó en la etapa fetal, donde claramente ninguno de estos factores fue relevante. Lo más gracioso es que, al confrontar a los adaptacionistas con este hecho (en discusiones en los blogs), tristemente no logran concederle ninguna relevancia; es una mera "coincidencia". No hay mejor ejemplo de cómo la ideología produce una cínica miopia intelectual incluso con los datos más evidentes. Hay quienes no se enterarían de la realidad aún si ésta les vomitase en los zapatos.

viernes, noviembre 07, 2008

¡Ya era hora!

¿Qué pasa cuando controlamos adecuadamente si hay fenotipo asociado a las sustituciones nucleotídicas "positivamente seleccionadas"?

Un comentario recientemente publicado en PNAS menciona un interesante estudio reciente de rhodopsinas que absorben diferentes longitudes de onda en muchas diferentes especies de peces que viven a diferentes profundidades o tienen diferentes conductas relacionadas con la luz. Se caracterizan muchos cambios no sinónimos que afectan la longitud de onda que absorben las rhodopsinas y que se corresponden con ele stilo de vida de cada especie de pez (es decir son "adaptativas"; véase este post previo sobre este tema ). Resulta una instancia idónea para poner a prueba de manera biológica la famosa "prueba estadística" de la selección positiva. Nos dice Austin Hughes:

"In fact, the results showed that the codon-based methods were 100% off-target. When Bayesian methods were applied to a set of closely related rhodopsin sequences, eight sites were identified as ‘‘positively selected.’’ Yet not one of these sites was among the 12 sites known to be involved in adaptive changes in rhodopsin sensitivity. Moreover, amino acid changes at these sites were shown experimentally to have no effect and thus almost certainly to lack any adaptive significance.These results support the theoretical prediction that, because of the faulty logic in their underlying assumptions, codon-based focus mainly on statistical artifacts rather than true cases of positive selection"

Hughes concluye:

"In recent years the literature of evolutionary biology has been glutted with extravagant claims of positive selection on the basis of computational analyses alone, including both codon-based methods and other questionable methods such as the McDonald-Kreitman test. This vast outpouring of pseudo-Darwinian hype has been genuinely harmful to the credibilit y of evolutionary biology as a science. It is to be hoped that the work of Yokoyama et al. will help put an end to these distressing tendencies."

Ya era hora!!

El comentario de Hughes está en el grupo yahoo decenio (PNAS 2008Hughes). Tienen que leerselo...acá sólo puse una fracción de sus demoledoras críticas.

Refs

Austin L. Hughes. The origin of adaptive phenotypes. PNAS 2008 105:13193-13194

lunes, octubre 20, 2008

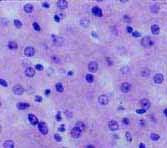

It's the SAME cell environment, stupid

slap in the face to epigenetics, the experiment describes what happens with some indicators of "gene expression" of human chromosome 21 in mouse hepatocytes; that is, human c21 has been incorporated into the genome of an experimental line of mice. They find that things such as the binding site of several transcription factors, and the general levels of transcription on the chromosome, are for the most (but not entirely) the same as in human hepatocytes. Their conclusion? The sequence of the human C21, rather than the epigenetic cell environment, is mostly responsible for "regulation" of its own expression. Hence, "It's the sequence, stupid".

slap in the face to epigenetics, the experiment describes what happens with some indicators of "gene expression" of human chromosome 21 in mouse hepatocytes; that is, human c21 has been incorporated into the genome of an experimental line of mice. They find that things such as the binding site of several transcription factors, and the general levels of transcription on the chromosome, are for the most (but not entirely) the same as in human hepatocytes. Their conclusion? The sequence of the human C21, rather than the epigenetic cell environment, is mostly responsible for "regulation" of its own expression. Hence, "It's the sequence, stupid".But, is it? It is well-known that all cells within the body contain the same sequence, but express very differently in different cell types, because of the different cell environments. It is interesting that the people at Science managed to wash this fact out of their brains, since it directly refutes that expression is determined in the sequence. Further, their conclusion is simply not logical because they are comparing cells with the exact same cell phenotype. The image shows micrographies from two liver sections; one is from mouse, the other is from human. Can anyone tell me which is which? The fact is, at the cell-histological level, most homologous tissues of mouse and human are undistinguishable.

Don't expect virtually identical cells to produce great differences in the expression of the same sequence just because you are comparing them in different species. Expect them to produce virtually identical gene expression. As simple as that.

Refs:

Wilson, M.D., Barbosa-Morais, N.L., Schmidt, D., Conboy, C.M., Vanes, L., Tybulewicz, V.L.J. Fisher, E.M.C., Tavaré, S., and Odom. D.T. 2008 Species-Specific Transcription in Mice Carrying Human Chromosome 21. Science 322: 434-438

Coller HA, Kruglyak L. 2008 Genetics.It's the sequence, stupid! Science. 322:380-1.

UPDATE

Check out this site on hepatocyte histology

Left is pig; right is raccoon

Phenotypic plasticity: This is mouse, fasted and glycogen-enriched

Phenotypic plasticity: This is mouse, fasted and glycogen-enriched And of course, human (from another site):

And of course, human (from another site):

lunes, octubre 06, 2008

Homeosis en dedos de dinosaurios

Estimados, los que me conocen ya saben que el asunto de las homeosis me gusta, y por varias razones (no sólo por las razones freaky-estéticas de ver una mosca con patas en la cabeza). Otras buenas razones son: 1) que demuestran la posibilidad de que distintas partes en el cuerpo de un embrión pueden cursar la misma vía epigenética 2) que muchas son eventos de transformación cualitativa, un sólo evento que no encaja con la noción de "acumulación selectiva" (véase esto y esto) 3) que muchas veces no tienen absolutamente ninguna consecuencia adaptativa que no sea rebuscada y poco creíble 4) que son demostrablemente ubicuas en la evolución cuando se hacen comparaciones filogenéticas (véase por ejemplo esto)

En este sentido durante los últimos tres años lejos de chile (felizmente ya estoy de vuelta) me he dedicado al tema de la inferencia de un "desplazamiento homeótico" que habria ocurrido en la evolución del ala de las aves, tal que los dedos 1,2 y 3 comenzaron a desarrollarse a partir de las condensaciones cartilaginosas que en otros amniotos se convierten en los dedos 2,3 y 4; este evento sólo puede concebirse como algo de un sólo paso, y su valor adaptativo está lejos de ser comprensible. Cabe recordar que existen publicadas opiniones adaptacionistas que pese a la contundende evidencia de la filogenia y de la embriología, morfología y expresión genética comparadas, han puesto en duda la ocurrencia de este evento sólo porque no tendría valor adapataivo, o peor aún, se ha dicho que este tipo de cambio requeriría mutaciones con efectos pleiotrópicos carcameativos que deteriorarían seriamente el fitness.

Bueno, pues a la pamplina panadaptacionista hay que responder con comparaciones filogenéticas bien hechas, nada más. Donde manda cladograma, no manda la especulación adaptacionista (tendencia que se impone, duélale donde les duela a los ecólogos evolutivos más "clásicos")

Así es como con gusto les presento mi más visible publicación hasta el momento, gratis para la descarga de Ud, familia y amigos, en PLoS ONE (journal de libre acceso que rápidamente se ha perfilado como el "nature de los pobres")

Sin más, les dejo el link para que los más curiosillos se lean este simpático ( y no muy largo!) artículo.

Saludos,

Alexander Vargas (aka Sander)

Selected Trackbacks:

ScienceDaily

Visualizing evolution

Awesome Science

Joe's random science blog

Talk rational

Hoxfulmonsters

Dinopantheon

Ornithomedia

LivedoorBlog

BeheFails

Faktaevolusi (Indonesia!)

Blog TCU

Electrónica Fácil (al fin algo en español)

lunes, septiembre 22, 2008

Más sobre filogenia animal: el mundo de las placas

Ya reclamábamos en este blog por la falta de los legendarios Placozoa en los "grandes muestreos gran" de filogenómica animal. Los placozoa, han sido tildados de animal ancestral mientras que otros han insitido en que se trata de una simplificación secundaria. A mí me ha parecido siempre que sí, que es un linaje antiguo; los tipos celulares que presenta son más o menos típicos de phyla basales de animales (incluso el aparato de actina-miosina de células contráctiles de placozoa pre-existe en "protozoa") Las dos capas celulares

Ya reclamábamos en este blog por la falta de los legendarios Placozoa en los "grandes muestreos gran" de filogenómica animal. Los placozoa, han sido tildados de animal ancestral mientras que otros han insitido en que se trata de una simplificación secundaria. A mí me ha parecido siempre que sí, que es un linaje antiguo; los tipos celulares que presenta son más o menos típicos de phyla basales de animales (incluso el aparato de actina-miosina de células contráctiles de placozoa pre-existe en "protozoa") Las dos capas celulares  de placozoa, ventral y dorsal, son notablemente diferentes. La condición de dos capas diferenciadas con un espacio al medio la vemos además en larvas de esponjas y tampoco es muy diferente a lo que se ve en la larva plánula de cnidarios. Otto Bütshcli en el sigo XIX, probablemente usando la más pura doctrina recapitulacionista, había adivinado (cuevazo más o cuevazo menos) una "plakula" ancestral y su invaginación en una gastrea antes de que se descubriera a los placozoa y su particular forma de invaginarse.

de placozoa, ventral y dorsal, son notablemente diferentes. La condición de dos capas diferenciadas con un espacio al medio la vemos además en larvas de esponjas y tampoco es muy diferente a lo que se ve en la larva plánula de cnidarios. Otto Bütshcli en el sigo XIX, probablemente usando la más pura doctrina recapitulacionista, había adivinado (cuevazo más o cuevazo menos) una "plakula" ancestral y su invaginación en una gastrea antes de que se descubriera a los placozoa y su particular forma de invaginarse.Podemos decir que los placozoa son una simplificación a partir de la larva de un animal más complejo, una esponja o cnidarios; o podríamos decir que se trata del metazoo más primordial conocido, cuyo perfil persiste en el embrión temprano de la ontogenia de los demás grupos (incluso blástula y gástrula temprana de bilateria).

En mi opinión las dos ideas contienen semilla de verdad. Consideremos la propuesta (aún vigente) el origen coanozooide de los

primeros metazoa, que va de la mano con la idea que los porifera serían parafiléticos, es decir, descendemos de las esponjas (Oh dioses del NSF: secuenciad esponajas hexactinélidas, YA!!!). Si todo eso está en lo correcto, entre un "coanozoa" colonial filtrador y esponjas, quizás no hay mucho lugar para una etapa placozoaria.Donde sí p

primeros metazoa, que va de la mano con la idea que los porifera serían parafiléticos, es decir, descendemos de las esponjas (Oh dioses del NSF: secuenciad esponajas hexactinélidas, YA!!!). Si todo eso está en lo correcto, entre un "coanozoa" colonial filtrador y esponjas, quizás no hay mucho lugar para una etapa placozoaria.Donde sí p arece haber más espacio, es en la transición de esponjas a epitheliozoa. Los adultos son muy diferentes, pero las larvas son parecidas; pueden descender los unos de los otros por vía de un estado paedomórfico en que la larva es el adulto.... exactamente, como placozoa. Y ESTE ancestro placozooide, ahora sí que sí, persistiría al más puro gusto de Haeckel en las plánulas y blástulas de la ontogenia de los cnidarios y bilateria.

arece haber más espacio, es en la transición de esponjas a epitheliozoa. Los adultos son muy diferentes, pero las larvas son parecidas; pueden descender los unos de los otros por vía de un estado paedomórfico en que la larva es el adulto.... exactamente, como placozoa. Y ESTE ancestro placozooide, ahora sí que sí, persistiría al más puro gusto de Haeckel en las plánulas y blástulas de la ontogenia de los cnidarios y bilateria.Y cómo anda todo esto con las grandiosas nuevas filogenias moleculares? Pues no tan mal, sin bien los infaltables agujeros en el muestreo taxoómico aún dejan las cosas medio inestables. Tenemos este trabajo reciente, altamente publicitado, basado en genomas completos:

Aunque placozoa sale como grupo hermano de epitheliozoa, todavía me aguantaré de saltar en una pata, debido al defectuoso muestreo taxonómico (La ínica esponja muestreada es una demospongita, Amphimedon. Monosiga es un coanoflagelado, Lottia es un grastrópodo. Nótese que con este muestreo no hay forma de descartar que los placozoa sean la larva paedomoórfica de una esponja. Esa hipótesis sigue vigente

Esta filogenia reciente de los coanozoa en cambio tiene un rico muestreo taxonómico y viene a confirmar con bastante seguridad que los coanoflagelados son el grupo hermano de los metazoa.

Referencias:

Srivastava, M., Begovic, E., Chapman, J., Putnam, N.H., Hellsten, U., Kawashima, T., Kuo, A., Mitros, T., Salamov, A., Carpenter, M.L., Signorovitch, A.Y., Moreno, M.A., Kamm, K., Grimwood, J., Schmutz, J., Shapiro, H., Grigoriev, I.V., Buss, L.W., Schierwater, B., Dellaporta, S.L., Rokhsar, D.S. (2008) The Trichoplax genome and the nature of placozoans. Nature 454:955-960. [doi:10.1038/nature07191]

Shalchian-Tabrizi K, Minge MA, Espelund M, Orr R, Ruden T, et al. (2008) Multigene Phylogeny of Choanozoa and the Origin of Animals. PLoS ONE 3(5): e2098. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002098

P.D. Hagamos un nucleo decenio de carne y hueso!! Sanders en Chile Lunes 29 de Septiembre, lo trae mote con huesillos light

sábado, septiembre 06, 2008

Palau update

Resulta que el paper del hombre de Palau era increíblemente mula. Ni siquiera las afirmaciones básicas sobre tamaño corporal y cerebral eran confiables, sino que estaban basadas en materiales demasiado fragmentarios e inferencias mal hechas. En resumen, el "hombre de Palau" es biológica y arqueológicamente igual a los seres humanos de la zona.

Resulta que el paper del hombre de Palau era increíblemente mula. Ni siquiera las afirmaciones básicas sobre tamaño corporal y cerebral eran confiables, sino que estaban basadas en materiales demasiado fragmentarios e inferencias mal hechas. En resumen, el "hombre de Palau" es biológica y arqueológicamente igual a los seres humanos de la zona.Cuando se publicó el paper del hombre de Palau, cometí el grave error de confiar en que las afirmaciones morfológicas (menor tamaño y microcefalia) eran correctas; sin embargo igual me indignó la baja calidad del paper en cuanto a cómo sustentaban sus afirmaciones filogenéticas. Dejé mi comentario al pie del paper en PLoS ONE, en este post, y en otros blogs. Ahí contestó John Hawks (revisor 1 de 2, el único a favor del paper de palau) explicando que los materiales eran insuficientes para un análisis más formal. Resulta que ni siquiera eran suficientes para determinar enanismo o microcefalia: como bien lo dice el título de este otro paper: "Small scattered fragments do not a dwarf make"

John hawks, dicho sea de paso, el "experto en evolución humana" (U. Wisconsin, que publica en PNAS) y que dió el ·"OK" a este trabajo (pese a la oposición del otro arqueólogo revisor) se dedica principalmente a detectar selección de genes a nivel de comparación de estructuras poblacionales y a nivel de secuencia primaria. Las explicaciones evolutivas que le gustan son fundamentalmente reduccionsistas- adaptacionistas, del corte preciso de la escuela de "psicología evolutiva", totalmente mulas: por ejemplo, "las enfermedades y miserias de la agricultura son responsables de enorme seleccion natural de genes en los últimos 5000 años" "tenemos microcefalinas con secuencias raras que heredamos de cruzas esporádicas con neandertales, y que han conferido enormes ventajas selectivas a sus poseedores". Sus coautores incuyen algunos que han argumentado que ha habido selección de genes para mayor inteligencia en judíos. En fin...sigo? Ciencia "de la buena"

Imagen de un hombre de Palau posando junto a sus descubridores de national geographic cinema corporation, quienes se defendieron "sí es un enano, lo que pasa es que es un enano gigante"

Imagen de un hombre de Palau posando junto a sus descubridores de national geographic cinema corporation, quienes se defendieron "sí es un enano, lo que pasa es que es un enano gigante"

miércoles, septiembre 03, 2008

Homologia e conservação hierárquica de estruturas

simple computer search for sequence similarity, nothing will be

found. In 1992 Bork et al.(8) used a sophisticated structure-

based sequence alignment, and they discovered that bacteria

did have genes related to actin. Actin is a member of a larger

superfamily that includes sugar kinases, the chaperone

hsp70, and the actin subfamily. These three subfamilies show

no recognizable sequence identity to each other in normal

pairwise alignments, but when the structures of hexokinase,

hsp70 and actin were determined by X-ray crystallography,

they were found to have virtually identical folding patterns.

Structural biologists interpret this to mean that the three

subfamilies evolved from a common protein ancestor.(9) Sugar

kinases and hsp70 were already known to exist in both

bacteria and eukaryotes because of their clear sequence

similarity: the bacterial proteins are 50 – 60% identical to their

eukaryotic homologs.(10) But the closest bacterial proteins to

eukaryotic actin showed less than 15% identity,(8) which is too

low for reliable identification. However, the more-sophisticated

alignment of Bork et al.(8) found three bacterial proteins that

appeared to be relatives of actin—FtsA, MreB and StbA (now

called ParM)"

A descoberta de proteínas homólogas a actina e tubulina em bactérias a partir de sua topologia - mas não de sua sequencia de nucleotídeos - nos mostra um ponto interessante em relação a dinâmica de transformação dos seres vivos. As transformações ocorrem de maneira hierárquica, ocorrendo de maneira semi-independente entre os diferentes niveis desde que conservada uma estrutura viável em cada nível. Ou seja, neste caso específico, as sequencias de nucleotídeos podem se transfomar desde que conservada as relações entre actina ou tubulina com outras moléculas, o que ocorre no nível das estruturas terciárias. Algo similar ocorre na relação entre conduta e morfologia. É comum que certas condutas, como o "bowing" em aves, se conservem em diferentes espécies apesar dos câmbios morfólogicos (e evidentemente, o revés é verdadeiro: mesmas morfologias permitem diferentes condutas). Também é o que ocorre em relação a formação das lentes nos olhos de anuros: em Rana fusca, como descrito por Spemann há mais de um século, a fomação das lentes no epitélio é induzida pela vesícula óptica. No entanto, em Rana esculenta não é necessário que ocorra indução. A mesma estrutura - um olho de Rana - é conservada apesar de transformações nos processos histológicos e moleculares.

Isto é essencialmente o que permite a ocorrência de "phenogenetic drift" - a morforfologia ou histologia é conservada, mas os processos moleculares subvernientes se tansformam. Eu, particularmente, prefiro não descrever este fenômeno como uma deriva do genótipo em relação ao fenótipo, como sugere o termo phenogenetic, pois isto presupõe um genótipo que determina um fenótipo. Seria preformacionista, pois supõe que a estrutual inicial determina as transformações durante a ontogenia, e reducionista pois supõe que os diferentes níveis de organização são controlados pelo nível molecular. Prefiro encarar todos estes fenômenos como uma deriva estrutural onde um nível pode se transformar desde que conservada sua operacionalidade e desde que sua realçao com os outros níveis não interrompa a operacionalidade destes.

De Beer, G. Homology, an unsolved problem, v.74. 1971

Erickson, H. P. Evolution of the cytoskeleton. Bioessays, v.29, n.7, p.668-77. 2007.

Weiss, K. M. e S. M. Fullerton. Phenogenetic Drift and the Evolution of Genotype–Phenotype Relationships. Theoretical Population Biology, v.57, n.3, p.187-195. 2000.

sábado, agosto 23, 2008

pajaritos con auto reconocimiento

Pensado antes como exclusivo de los primates... pero visto ahora también (y únicamente) en este pajarito.

sábado, agosto 16, 2008

Conduta e Evolução dos Cetáceos

Nature 450, 1190-1194 (20 December 2007)

Whales originated from aquatic artiodactyls in the Eocene epoch of India

J. G. M. Thewissen1, Lisa Noelle Cooper1,2, Mark T. Clementz3, Sunil Bajpai4 & B. N. Tiwari

"The modern artiodactyl morphologically most similar to Indohyus is probably the African mousedeer Hyemoschus aquaticus. Hyemoschus lives near streams and feeds on land, but flees into the water when danger occurs40. Indohyus had more pronounced aquatic specializations than Hyemoschus does, and it probably spent a considerably greater amount of time in the water either for protection or when feeding. As indicated by the evidence from stable isotopes, Indohyus spent most of its time in the water and either came onshore to feed on vegetation (as the modern Hippopotamus does) or foraged on invertebrates or aquatic vegetation in the same way that the modern muskrat Ondatra does.

Raoellids are the sister group to cetaceans, and this implies that aquatic habitats originated before the Order Cetacea. The great evolutionary change that occurred at the origin of cetaceans is thus not the adoption of an aquatic lifestyle. Here we propose that dietary change was the event that defined cetacean origins; this is consistent with the cranial and dental synapomorphies identified. Molars of Indohyus are markedly different from those of pakicetids, and it is widely assumed that pakicetids ate aquatic prey18, 23.

Our working hypothesis for the origin of whales is that raoellid ancestors, although herbivores or omnivores on land, took to fresh water in times of danger. Aquatic habits were increased in Indohyus (as suggested by osteosclerosis and oxygen isotopes), although it did not necessarily have an aquatic diet (as suggested by carbon isotopes). Cetaceans originated from an Indohyus-like ancestor and switched to a diet of aquatic prey. Significant changes in the morphology of the teeth, the oral skeleton and the sense organs made cetaceans different from their ancestors and unique among mammals."

Poderia ser diferente? Os pobres cetaceos, a partir de uma nova conduta, se tornaram aprisionados en el mar, como Glaucus: "According to Ovid, Glaucus began life as a mortal fisherman living in the Boeotian city of Anthedon. He discovered by accident a magical herb which could bring the fish he caught back to life, and decided to try eating it. The herb made him immortal, but also caused him to grow fins instead of arms and a fish's tail instead of legs forcing him to dwell forever in the sea".

By the way, hoje morreu o grande compositor brasileiro Dorival Caymmi, que, junto a Jorge Amado, escreveu a linda canção "Doce é morrer no mar".

domingo, agosto 10, 2008

Advertencias de Darwin sobre selección natural

lunes, agosto 04, 2008

Fisiologia (Cardíaca) Desenvolvimental II

The aim of the present study is to examine whether the formation of the cranial and cervical flexures is involved in the process of cardiac looping, and whether looping anomalies are causally involved in the development of cardiac malformations. For this purpose, the formation of the cranial and cervical flexures was experimentally suppressed in chick embryos by introducing a straight human hair into the neural tube. In the experimental embryos, the absence of the cervical flexure, alone or in combination with a reduced cranial flexure, was always associated with anomalies in the looping of the tubular heart.

Os autores, intrigados, discutem:

These results are in accord with the hypothesis that certain positional and morphological changes of the embryonic heart loop are caused by the formation of the head flexures (His 1881 ; Patten 1922). However, we must concede that there are experimental findings published by Waddington (1937) and Flynn et al. (1991) which seemingly support a totally different hypothesis, namely that the curvature of the cervical region is caused by the positional changes of the heart loop. Our results do not give direct information as to which of the two correlated processes - embryonic flexures and cardiac looping - is the cause and which is the effect.

A dúvida dos autores surge desde um ponto de vista mecanicista dos seres vivos. No entanto, o coração contribui para a dobramento da cabeça e o dobramento da cabeça contribui para a formação do coração. Organismos possuem uma organização circular que os diferencia de máquinas. Como diria um velho filósofo alemão: "Organismos são seres em que as partes são meio e fim". Ou:

domingo, julio 27, 2008

Phyloepigenetics IV: Lagartija y nemátodo

Excerpts!

"In 1971 five adult pairs of this species were moved from the small islet of Pod Kopiste (0.09 km2) to the nearby Pod Mrcaru (0.03 km2) by Nevo and coworkers (...). Although the islet of Pod Mrcaru was originally inhabited by another lacertid lizard species (Podarcis melisellensis), repeated visits (twice yearly over the past three years, beginning in 2004) show that this species has become extinct on Pod Mrcaru. Genetic mitochondrial DNA analyses indicate that the lizards currently on Pod Mrcaru are indeed P. sicula and are genetically indistinguishable from lizards from the source population"

"Differences in head size and shape also translate into significant dif ferences in bite force bet ween populations. Our data show that P. sicula lizards consume more plant material on Pod Mrcaru compared with the ancestral population on Pod Kopiste"

"This shift to a predominantly plant-based diet has resulted in the dramatic evolution of intestinal morpholog y. Morphological analysis of preserved specimens shows the presence of cecal valves (Fig. 4) in all individuals, including a hatchling (26.4-mm snout-vent length, umbilical scar present) and a very young juvenile (33.11-mm snout-vent length) examined from Pod Mrcaru."

"The fact that 1% of all currently known species of squamates have cecal valves (13, 14) illustrates the unusual nature of these structures in this population"

"Cecal valves slow down food passage and provide for fermenting chambers, allowing commensal microorganisms to convert cellulose to volatile fatt y acids (15, 16). Indeed, in the lizards f rom Pod Mrcaru, nematodes were common in the hindgut but absent from individuals f rom PodKopiste"

"Because of the larger food base available and the increase in the predict abilit y of the food source, lizard densities on Pod Mrcaru are much greater (..) lizards on Pod Mrcaru do no longer appear to defend territories. Moreover, changes in foraging style (browsing versus active pursuit of mobile prey) and social structure may also have resulted in the dramatic changes in limb proportions and maximal sprint speed previously documented for this population"

"Although the presence of cecal valves and large heads in hatchlings and juveniles suggests a genetic basis for these differences, further studies investigating the potential role of phenotypic plasticity and/or maternal effects in the divergence bet ween populations are needed"

Herrell no discute mucho qué tan relevante puede ser la simbiosis con un nemátodo. Veamos un ejemplo de anfibios

Effects of the nematode Gyrinicola batrachiensis on development, gut morphology, and fermentation in bullfrog tadpoles (Rana catesbeiana): a novel mutualism

Gregory S. Pryor *, Karen A. Bjorndal J. Exp. Zool. 303A:704-712, 2005.

Abstract

We describe a novel mutualism between bullfrog tadpoles (Rana catesbeiana) and a tadpole-specific gastrointestinal nematode (Gyrinicola batrachiensis). Groups of tadpoles were inoculated with viable or nonviable nematode eggs, and development, morphology, and gut fermentation activity were compared between nematode-infected and uninfected tadpoles. Nematode infection accelerated tadpole development; the mean time to metamorphosis was 16 d shorter and the range of times to metamorphosis was narrower in nematode-infected tadpoles than in uninfected tadpoles. At metamorphosis, infected and uninfected bullfrogs did not differ in body size or condition. Colon width, wet mass of colon contents, and concentrations of most fermentation byproducts (short-chain fatty acids: SCFAs) in the hindgut were greater in infected tadpoles. Furthermore, in vitro fermentation yields for all SCFAs combined were over twice as high in infected tadpoles than in uninfected tadpoles. One explanation for accelerated development in infected tadpoles is the altered hindgut fermentation associated with the nematodes. Energetic contributions of fermentation were estimated to be 20% and 9% of the total daily energy requirement for infected and uninfected tadpoles, respectively. Infection by G. batrachiensis nematodes potentially confers major ecological and evolutionary advantages to R. catesbeiana tadpoles. The mutualism between these species broadens our understanding of the taxonomic diversity and physiological contributions of fermentative gut symbionts and suggests that nematodes inhabiting the gut regions of other ectothermic herbivores might have beneficial effects in those hosts.

Si bien algunos nemátodos son parásitos en reptiles, otros no lo son:

Oecologia. 2006 Dec;150(3):355-61. Epub 2006

O'Grady SP, Dearing MD. Isotopic insight into host-endosymbiont relationships in Liolaemid lizards

Nitrogen isotopes have been widely used to investigate trophic levels in ecological systems. Isotopic enrichment of 2-5 per thousand occurs with trophic level increases in food webs. Host-parasite relationships deviate from traditional food webs in that parasites are minimally enriched relative to their hosts. Although this host-parasite enrichment pattern has been shown in multiple systems, few studies have used isotopic relationships to examine other potential symbioses. We examined the relationship between two gut-nematodes and their lizard hosts. One species, Physaloptera retusa, is a documented parasite in the stomach, whereas the relationship of the other species, Parapharyngodon riojensis (pinworms), to the host is putatively commensalistic or mutualistic. Based on the established trophic enrichments, we predicted that, relative to host tissue, parasitic nematodes would be minimally enriched (0-1 per thousand), whereas pinworms, either as commensals or mutualists, would be significantly enriched by 2-5 per thousand. We measured the (15)N values of food, digesta, gut tissue, and nematodes of eight lizard species in the family Liolaemidae. Parasitic worms were enriched 1+/-0.2 per thousand relative to host tissue, while the average enrichment value for pinworms relative to gut tissue was 6.7+/-0.2 per thousand. The results support previous findings that isotopic fractionation in a host-parasite system is lower than traditional food webs. Additionally, the larger enrichment of pinworms relative to known parasites suggests that they are not parasitic and may be several trophic levels beyond the host.

Correlating diet and digestive tract specialization: Examples from the lizard family Liolaemidae

Shannon P. O’Gradya, Mariana Morandob, Luciano Avilab and M. Denise Dearinga

Zoology 2005, 108 : 201-210

Abstract

A range of digestive tract specializations were compared among dietary categories in the family Liolaemidae to test the hypothesis that herbivores require greater gut complexity to process plant matter. Additionally, the hypothesis that herbivory favors the evolution of larger body size was tested. Lastly, the association between diet and hindgut nematodes was explored. Herbivorous liolaemids were larger relative to omnivorous and insectivorous congeners and consequently had larger guts. In addition, small intestine length of herbivorous liolaemids was disproportionately longer than that of congeners. Significant interaction effects between diet and body size among organ dimensions indicate that increases in organ size occur to a greater extent in herbivores than other diet categories. For species with plant matter in their guts, there was a significant positive correlation between the percentage of plant matter consumed and small intestine length. Herbivorous liolaemids examined in this study lacked the gross morphological specializations (cecum and colonic valves) found in herbivores in the families Iguanidae and Agamidae. A significantly greater percentage of herbivorous species had nematodes in their gut. Of the species with nematodes, over 95% of herbivores had nematodes only in the hindgut. Prevalence of nematodes in the hindgut of herbivores was 2× that of omnivores and 4× that of insectivores.

Los dichosos nemátodos se encuentran en todas las especies de reptil que tienen válvulas cecales

Preguntas:

Todo este cambio, en sólo 34 años.... es acaso una acumulación por selección direccional de varios genes? Grano fino, o grano grueso?

Cuánto de este cambios fenotípico drástico se debe más bien al efecto inmediato de diferentes condiciones epigenéticas, como la mentada asociación con el nemátodo?

jueves, julio 24, 2008

Natural drifting is not a crime

han citado el trabajo de Maturana y Mpodozis (1992, 2000 "El origen de las especies por medio de la deriva natural" ) como una fuente de daño a la biología evolutiva en Chile. Es una discusión de ideas, pero el tema moral-acusatorio nos lleva a la vez a una discusión sobre personas (Sorpresa! esos señores Maturana y Mpodozis). La propuesta de Nespolo y Medel es simple: sencillamente no hay lugar para la deriva natural en la ciencia (y por esto, es dañina, sobre todo si la enseñan en pregrado).

han citado el trabajo de Maturana y Mpodozis (1992, 2000 "El origen de las especies por medio de la deriva natural" ) como una fuente de daño a la biología evolutiva en Chile. Es una discusión de ideas, pero el tema moral-acusatorio nos lleva a la vez a una discusión sobre personas (Sorpresa! esos señores Maturana y Mpodozis). La propuesta de Nespolo y Medel es simple: sencillamente no hay lugar para la deriva natural en la ciencia (y por esto, es dañina, sobre todo si la enseñan en pregrado).Sin embargo, la idea de esta "mala influencia" está refutada por los hechos. Somos varios los que hemos pasado por el lab de biología del conocer y que desarrollamos investigación en journals de evolución. ¿Cómo es que se llega a ese tipo de acusaciones, entonces?

La deriva no es un trabajo altamente técnico como el que pueda publicar Nespolo en Evolution. Todos tenemos un "esquema" complejo que inspira nuestra investigación, compuesto de varias ideas conectadas y el cual conviene mucho discutir y reinventar. Esto por lo general no es posible por medio de un sólo trabajo o review técnico, y muchas veces se hace en libros, publicaciones ocasionales y revistillas humildes. Es lo que se llama "inspirational writing" y hacerlo no constituye una abominable práctica anticientífica. Más bien, es una de las tradiciones más queridas de la biología evolutiva (sea del color que sea!).

Tampoco es que necesitemos de la venia académica especial de Medel o Nespolo. Las nociones evolutivas de la deriva natural (Maturana y Varela 1973, 1984, Maturana y Mpodozis 1992) no son ajenas a la discusión teórica de la biología evolutiva (Balon 2003, Roth 1982). También se cita el aporte de Maturana y Varela en temáticas tan importantes para la comprensión de la evolución como lo es la discusión sobre el rol de los genes (Neuman-Held 2000) y la auto-organización en los seres vivos (Kauffman 1996). Los escritos de Maturana y coautores han sido traducidos a distintos idiomas (incluyendo la deriva natural) y han producido discusión en varias ramas de la biología, una de las cuales es la biología evolutiva. Otra es el campo de la abiogénesis (origen de la vida; Luigi Luisi 2006, Margulis 2000).

Medel y Nespolo se concentran en la acusación central de que M&M es un repudiable trabajo no-científico. Como es un trabajo que supuestamente no vale la pena, la discusión del contenido es notablemente rudimentaria y selectiva. Sólo dan a entender dos cosas 1) lo encuentran confuso y mal escrito, que no se entiende y/o 2) no perdonan el destronamiento de la selección natural como principal mecanismo evolutivo o "fuerza" detrás de la adaptación.

Ni una palabra sobre autopoiesis, genotipo total, el campo epigénico, la noción sistémica de herencia, el nicho ontogénico...todos temas recurrentes en M&M y en este blog. No dan la menor luz de comprender el "core" de la propuesta de M&M.

Como el epicentro de la acción es la facultad de ciencias de la universidad de chile, resulta que tenemos muchos amigos en común algunos de los cuales sufren cuando corren estas discrepancias y que desean, correctamente, que seamos todos amigos. Pero tengan en cuenta que nadie les ha hecho a ellos jamás acusaciones públicas (y menos en medios académicos) de tener ideas no científicas y de dañar a la ciencia en Chile. Al acusar de estas cosas, no es como que ellos se dejen a sí mismos mucha opción que no sea el rechazo absoluto

Onde Está o organismo?

Ref: Nurse, P. Life, logic and information. Nature 454: 424-426

martes, julio 22, 2008

What is so informative about information?

Carlos M. Hamame, Diego Cosmelli, and Francisco Aboitiz (2007) . Comentario sobre: "Précis of Evolution in Four Dimensions" Eva Jablonka and Marion J lamb

Behavioral and Brain Sciences 30: 371 – 372

Abstract: Understanding evolution beyond a gene-centered vision is a fertile ground for new questions and approaches. However, in this systemic perspective, we take issue with the necessity of the concept of information. Through the example of brain and language evolution, we propose the autonomous systems theory as a more biologically relevant framework for the evolutionary perspective offered by Jablonka & Lamb

Hablando del tremendo daño a Chile con que según Medel (2008) carga el legado de Maturana, ya mencionaba anteriormente que por aquel fatídico templo de endoctrinamiento que era el lab "el rayo" había pasado Francisco Aboitiz. Ahora, entiéndase bien: Aboitiz tiene "ADN" darwinista. Al menos donde quedamos la última vez, la cuestión era la selección natural, y le molestaba el manejo de M&M de ese tema.

En realidad, pasar por el lab de Maturana no es un lavado de cerebro. Cada cual termina recogiendo lo que le guste, aunque no esté de acuerdo con otra cosa. Por lo general, se quedan con algo. Es por eso que fue grato leer el artículo arriba citado, donde estos autores producen una elegante crítica de Jablonka y Lamb muy en sintonía con nuestra forma de pensar:

"However, while the authors dispute the gene-centered notion and consider evolution as a systemic multilayered phenomenon, we believe they fall short in one critical aspect: J&L rely heavily on the notion of “information transmission” in a rather loose manner. Their approach is liable to the argument that in order to have any such thing, one needs a transmitter, a message, and a receiver – something that is not easily found when dealing with biological phenomena"

"One influential hypothesis states that living systems are those that maintain organizational closure: they are constituted by networks of self-sustaining processes, regardless of the materials used to instantiate such loops; that is, they are autonomous systems (Maturana & Varela 1973; Varela 1979). When one understands organisms this way, the notion of information transmission becomes less appealing: a closed system cannot “have” information in itself"

El artículo de Hamame et al 2007 está en el grupoyahoo bajo el nombre "Précis of Evolution in Four Dimensions" Muy recomendado

Sobre las Malas Influencias de la Deriva Natural

Después de muchas batallas editoriales, por fin ha salido en papel el quinto artículo y final de mi tesis acerca del aprendizaje olfativo en la búsqueda de pareja en avispas parasitoides (en la base de datos).

Estos trabajos exploran el valor del aprendizaje en diferentes estados de la ontogenia del insecto y como estas instancias están relacionadas con la preferencia de hábitat reproductivo y la fidelidad al hospedero.

En el caso de insectos que viven con fuerte dependencia a otro organismo, como por ejemplo una planta huésped, este tipo de aprendizaje podria estar relacionado con del origen de razas especializadas a hospederos y especiación simpátrica. Esto ha comenzado a reconocerse por varios autores contemporaneos trabajando en interacción insecto-planta (ver referencias en post ¿Búfalo o Buey? por ejemplo).

Estos experimentitos fueron enriquecido por las interesantes conversaciones sobre evolución y comportamiento con Jompoma y Marín en la Chile, las discusiones sobre especiación simpatrica en insectos con el querido Profesor Frías en la UMCE, y esas agradables tardes de viernes del Decenio en el Rayo.

¡Viva la Revolution!

Cristian Villagra, PhD

Postdoctoral Associate

Dept. Neurobiology and Behavior

Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

lunes, julio 14, 2008

Fisiologia (Cardíaca) Desenvolvimental

Lembro-me que quando o Mpodozis esteve aqui em Florianópolis ele comentou que deveríamos entender um fígado embrionário no contexto da dinâmica do embrião, e não pensando no que ele deverá estar fazendo enquanto um fígado no animal adulto. Por este motivo, me agradou muito encontrar esse artigo que fala de uma “Fisiologia cardíaca desenvolvimental” – termo criado pelo autor, que explicita sua preocupação em compreender o que faz o coração no embrião, no contexto do desenvolvimento, não como um órgão se preparando para bombear sangue no futuro! Isso é muito relevante, pois quase todas as descrições do desenvolvimento cardíaco têm esse viés de explicar a formação de um órgão para bombear sangue. É explicação baseada nas expectativas do observador, que remete ao futuro, e que desreipeita uma lógica de construção histórica.

Agora falando de fato sobre o assunto, vejam vocês, que curioso: nos períodos mais iniciais do desenvolvimento embrionário, o embrião realiza suas trocas gasosas através de uma simples difusão; até que a partir de um certo tamanho isso não é mais possível e então se observa que há ali agora uma circulação sanguínea e um coração batendo! Então isso basta para se dizer que o coração surgiu para manter a oxigenação. Mas vejam neste gráfico. Ao contrário do que se esperava desde uma perspectiva funcionalista (painel superior da figura), o coração começa a bater ANTES do embrião atingir esse tamanho que impossibilita a difusão (figura do painel inferior).

Quer dizer, nos períodos iniciais está lá o animalzinho fazendo difusão e batendo seu coração... Tira-se fora o coração aí e o que se passa? O embrião continua vivendo e oxigenando seus tecidos. O coração surge num contexto independente desta função de nutrição de oxigênio. Não surge para realizar esta função, que atribuímos ao coração no adulto. O que faz o coração aí? Para entender isso, precisamos entender seu contexto de relações e sua história, não sua finalidade (sua função), por isso a explicação funcionalista não nos serve.

Então encontrei este elegante manuscrito de Waddington (1937): “THE DEPENDENCE OF HEAD CURVATURE ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE HEART IN THE CHICK EMBRYO”, em que ele remove o coração do embrião para observar as conseqüências disso no resto desenvolvimento. Os principais achados dele eu reproduzo aqui:

"1. The heart was removed from chick embryos of seven to twelve somites, and the embryos cultivated in vitro. The operation abolished the normal twisting of the anterior part of the embryo on to its left side and the general bending of the brain region into an arc. These two processes therefore seem to be dependent on the normal development of the heart.

2. The embryos showed a bending of the forebrain relative to the midbrain, which is therefore independent of the development of the heart.

4. The lateral evaginations of the foregut and the visceral arch mesenchyme underwent the first stages of differentiation in atypical positions, seemingly independently of each other or of any other structures

Enfim, compartilho com vocês este raro momento em que se mira a construção de um órgão sem se preocupar com a sua finalidade, sem vê-lo como um trânsito para sua futura função.

Abraços,

Gustavo

Referencias

Burggren, W., Crossley, D. A. Comparative cardiovascular development: improving the conceptual framework. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology - Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. Volume 132, Issue 4, August 2002, Pages 661-674.

Waddington C_1937.The dependence of head curvature on the development of the heart in the chick embryo. J Exp Biol

14:229]231

jueves, julio 10, 2008

¿Búfalo o Buey?

“..Although Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution laid the foundations of modern biology, it did not tell the whole story. Most remarkably, The Origin of Species said very little about, of all things, the origins of species. Darwin and his modern successors have shown very convincingly how inherited variations are naturally selected, but they leave unanswered how variant organisms come to be in the first place..”

References:

Agrawal AA. (2001) Phenotypic Plasticity in the Interaction and Evolution of Species. Science, 294.

Beltman JB., P Haccou & CT Cate (2004) Learning and Colonization of New Niches, A first step towards speciation. Evolution, 58, pp. 35–46.

Donohue K. (2004) Niche construction through phenological plasticity: life history dynamics and ecological consequences. New Phytologist. Vol 166: 83-92.

Dre`s M & Mallet J (2002) Host races in plant-feeding insects and their importance in sympatric speciation. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 357, 471–492.

Hegrenes S. (2001) Diet-induced phenotypic plasticity of feeding morphology in the orangespotted sunfish, Lepomis humilis. Ecology of Freshwater Fish.10: 35–42.

Jablonka E. & Lamb’ M. J. (1998) Epigenetic inheritance in evolution. J. evol. biol. 11 159-183.

Maturana-Romesin H & Mpodozis J (2000) The origin of species by means of natural drift. Rev. chil. hist. nat. v.73 n.2.

Stamps J. (2003) Behavioural processes affecting development: Tinbergen’s fourth

question comes of age. Behaviour. 66:1-13.

Trussell GC (2000) Phenotypic Clines, Plasticity, and Morphological Trade-offs in an intertidial Snail. Evolution, 54: 151–166.