Figure 1: hollow thorn Mesoamerican Acacia.

Following the idea of the proceses that allow inter-organims interactions to move from facultative to obligate, lets take a look at the amazing case of acacia trees and its Pseoudomyrmex ants asociates.

Among tropical plants, around 100 genera host specialized ant colonies in structures called “domatia” and in part of these cases, plants also provide these ants with food. Ants in this association exhibits intensive territorial and cleaning behavior over the plant. This has as a consequence the expulsion of other herbivores and their eggs, and the detachment of invasive vegetation and sometimes fungi as well. Thus this relationship has been described as mutualistic.

Extensive revision of this case has suggested that the trait making the interaction between myrmecophyte plants and ants obligatory is usually the formation of domatia (nesting structures) on the plant. Domatia usually are located on hollow stem and shoots, hollow thorns (like in the Figure 1), in leaf pouches, petioles or even on fruits. Additionally, some myrmecophytes present plant derived food rewards like food bodies and extrafloral nectar (EFN) (See Figure 2).

Figure 2: Extrafloral nectar producing structures (upper) and food bodies on acacia tree, visited by Pseoudomyrmex ants.

However, despite these plants and ants seems to be vitally dependent on such interaction, the mutualistic association, even for the ones considered obligate, is transferred horizontally: both partners reproduce independently and the association has to be established di novo in each subsequent generation.

Figure 3: Phylogenetic reconstruction of section from Acacia subgenus includying facultative (grey) and obligate ant interacting plants (orange), based on combined data matrix of chloroplast DNA markers, AFLP cluster analysis (from Heil et al. 2004).

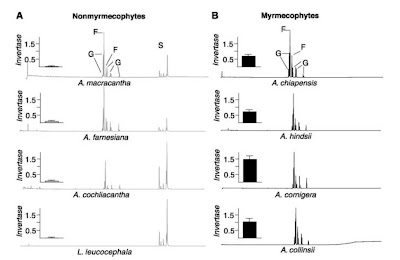

Another trait that has been proposed as relevant of the establishment of obligate plant-ant association correspond to the extrafloral nectar production. Inside the subgenus Acacia, both non-myrmecophyte and myrmecophyte plants release extrafloral nectar (see Figure 3). But the details of how this trait is expressed make the whole difference. In non specialized plants extrafloral nectar secretion respond positively to mechanical damage, herbivory or to the exogenous application of 1mM solution of the plant hormone jasmonic acid (also involve in other plant-herbivory chemical responses). By the other hand, in general, specialized myrmecophytes exhibit a constitutive (and comparatively slow) nectar release, irrespectively of whether exogenous stimuli applied. Thus the attraction of non-specialized nectar feeders (like unspecialized ants) seems to be related to the plant herbivory response machinery in non-myrmecophytes plants with EFN production, while on myrmecophytes this trait continuously expressed. Moreover, nectar composition on facultative EFN producers has three main sugars: glucose, fructose and sucrose, while myrmecophyte plants lacks sucrose (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Chromatograms of relative abundance of sugars in the EFN from non specialized (left) and myrmecophyte acacias (from Heil et al. 2005). Peaks identified as G; glucose, F: fructose, S: sucrose. Insert on left of graph is invertase activity in the nectar for each plant expresed as ug glucose released per ul of EFN per minute.

This is the result of post-secretory hydrolysis of the nectar sucrose on the obligate ant-interacting plant due to invertase activity. Sucrose and other di and trisaccharides are identified as a highly attractive sugars for many non-specialized ants. In nectar choice experiments using non specialized ants and myrmecophyte specialized ants it has been demonstrated that the addition of sucrose to the nectar of the derived myrmecophyte acacia, had triggered the attraction of non specialized ants, that previously (without sucrose) will not be attracted to the nectar of these plants but to the non-myrmecophyte ones. Contrarily, specialized ants are significantly attracted to nectar without sucrose. Analysis of digestive enzymes on these ants has repeatedly demonstrated the lower activity of invertases in extracts of the digestive systems of Pseoudomyrmex specialized ants, while the facultative plant interacting ants from the same genus, P. gracilis, showed greater invertase activity, this specie can actually live independently of acacia trees. Thus, this suggest that the obligate horizontally transmitted Acacia-Ant association is also supported by the transference of the hydrolysis process to the host plant in the evolution of this tight plant-insect association.

Cristian Villagra

PS: Follow the link to see a video of this fascinating interaction from the documental series The Secret Life of Plants.

References:

Agrawal AA. 1998. Leaf damage and associated cues induce aggressive ant recruitment in a neotropical ant-plant. Ecology 79: 2100–2112.

Heil M, Greiner S, Meimberg H, Krüger R, Noyer J-L, Heubl. G, Linsenmair KE, Boland W. 2004. Evolutionary change from induced to

constitutive expression of an indirect plant resistance. Nature 430: 205–208.

Heil M, Rattke J, Boland W. 2005. Post-secretory hydrolysis of nectar sucrose and specialization in ant/plant mutualism. Science 308:560–563.

Heil M. 2008 Indirect defence via tritrophic interactions. New Phytologist 178: 41–61.